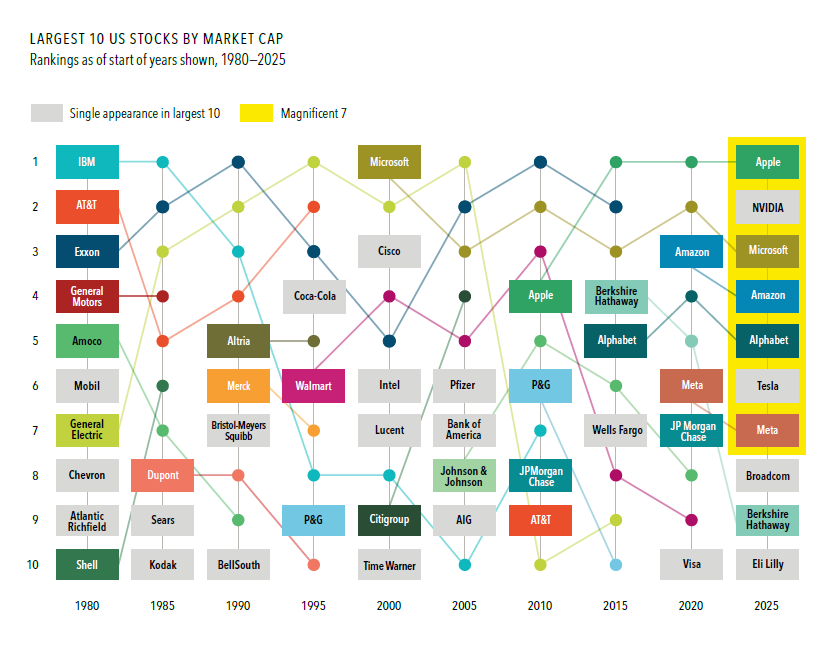

The democratisation of investing has transformed the financial landscape. Where once only institutional investors had access to sophisticated investment vehicles, today's retail investors can build diversified portfolios with a few clicks on their smartphones. Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have been at the forefront of this revolution: in the United States, they now represent half of all listed funds[1], a remarkable shift that reflects their popularity and accessibility.

The investment supermarket has expanded exponentially, offering strategies across listed and unlisted assets, domestic and international markets, and countless sectors and themes. From tech giants like Apple and Nvidia to broad market indices, bond funds to commodity trackers, the barriers to entry have never been lower.

A generation ago, building a globally diversified portfolio required significant wealth and professional intermediaries. Today, it requires a brokerage account and an internet connection.

But more choice doesn't automatically mean better outcomes. In New Zealand, there's a growing cohort of DIY investors who are playing the gross game when they should be playing the net game. They're watching their portfolio balances grow, celebrating double-digit returns, and comparing performance with friends… all whilst ignoring the substantial tax implications that will ultimately determine their real wealth accumulation.

The Bracket Creep Reality

New Zealand's tax landscape has shifted dramatically, yet many investors haven't adjusted their thinking accordingly. A significant number of Kiwis now find themselves in the 33% tax bracket (income between $70,000 and $180,000) or even the 39% bracket for those earning over $180,000, often without realising it until after 31 March when their tax returns are typically filed.[2]

This isn't always due to massive salary increases or career progression. Bracket creep, driven by wage inflation without corresponding tax threshold adjustments, is quietly pushing more New Zealanders into higher tax brackets each year[3]. As wages rise to keep pace with the cost of living, the tax system captures an increasingly large slice of that income. What once seemed like a tax bracket reserved for high earners has become surprisingly accessible to middle-income professionals.

But there's another factor many overlook when calculating their tax position: total earnings extend far beyond salary. Consider the full picture of your financial life. That cash sitting in the bank, even at relatively low interest rates, generates taxable income[4]. It might not seem like much on an individual transaction basis, but across multiple accounts and a full tax year, it adds up.

Trust distributions, company dividends, rental income from investment properties, and profits from share trading; these all contribute to your taxable income.

Many investors are genuinely surprised when they discover their effective tax rate is higher than anticipated, simply because they've been thinking about salary in isolation rather than total taxable income.

The Hidden Consequence

When you buy shares in Nvidia, Apple, or any other direct shareholding, or when you invest in ETFs tracking international markets, you're creating taxable events. Under New Zealand's tax rules, particularly the Foreign Investment Fund (FIF) regime, these investments generate tax obligations that must be included in your annual return[5].

The FIF rules are complex and often misunderstood. Many investors assume they only pay tax when they sell. In reality, they may be liable for tax on deemed income each year, regardless of whether they've sold anything. Yet a startling number of investors either don't realise this or don't adequately account for it in their investment strategy.

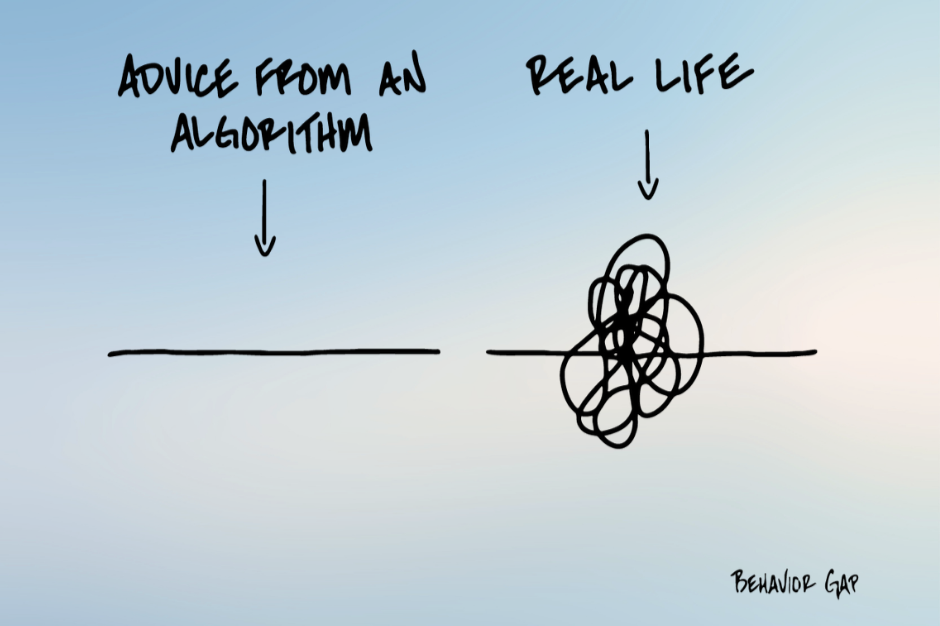

They're focused on gross returns (the headline numbers showing how much their portfolio has grown) without applying a tax overlay to understand their true, net position. They celebrate when their tech stock portfolio rises 25%, but forget to calculate what that means after tax obligations are met.

How We Got Here

For roughly 25 years, New Zealand maintained a relatively flat tax structure with a top rate of 33%[6]. The tax environment was stable and predictable. Investors could make reasonably informed decisions knowing that their tax position would remain relatively constant.

But the introduction of the 39% top tax rate in 2021[7], combined with the absence of inflation indexing for tax brackets, has fundamentally changed the game. Each year, more New Zealanders cross into higher tax brackets not because they're genuinely wealthier in real terms, but simply because thresholds haven't kept pace with inflation.

The compounding effect is significant. A professional who was comfortably in the 30% bracket (or lower) a decade ago might now find themselves in the 33% or even 39% bracket, despite their real purchasing power having barely changed. The tax burden has increased substantially, yet investment strategies have often remained unchanged.

Gross Returns vs Net Reality

An investment delivering a 10% gross return might sound attractive, but if you're in the 39% tax bracket and a significant portion of that return is taxable under the FIF rules, your net return tells a very different story. Suddenly that 10% might be closer to 6% or 7% after tax. It’s still positive, but materially different from the headline figure.

This distinction becomes even more critical when comparing investment options. A lower-gross-return investment with tax advantages might deliver superior after-tax returns compared to a higher-gross-return investment that's tax-inefficient for your circumstances.

You don't want to win the battle only to lose the war. Chasing gross returns without understanding the net outcome is a pyrrhic victory – it looks impressive on portfolio statements but delivers disappointing real-world results when tax time arrives.

The Silo Trap

Even when investors recognise the need for professional advice, they can fall into another trap: the silo regime. Perhaps influenced by barbecue conversation about diversifying across advisers – “don't put all your eggs in one basket, mate” – some investors split their portfolio. They might allocate $750,000 here with one adviser, another substantial chunk there with a second, and perhaps a third portion elsewhere for good measure.

The logic seems sound on the surface. After all, diversification is a fundamental investment principle, so why not diversify your advisers too? It provides a sense of security, multiple perspectives, and perhaps even keeps each adviser "honest" through implicit competition.

You’re essentially asking each adviser to play with one hand tied behind their back.

No single adviser in this fragmented arrangement understands your complete tax position. They can't see the full picture of your income sources, your various investment vehicles, or how different components of your portfolio interact from a tax perspective. They're optimising for their slice of your wealth without any visibility into the whole.

One might be selecting investments that generate substantial taxable income, unaware that another adviser is doing the same thing, pushing you into a higher tax bracket than necessary. Or they might be duplicating strategies, eliminating the diversification benefits you sought by splitting your portfolio in the first place.

Each adviser might be doing an excellent job with their portion, yet your overall outcome remains suboptimal because no one is orchestrating the tax efficiency of the complete picture[9].

It's the financial equivalent of having multiple chefs each cooking one course of a meal without coordinating the menu. You might end up with three excellent dishes that don't work together at all.

Why You Need a Financial Adviser

Professional guidance matters. And not just any adviser, but one who can see your complete financial picture and implement a coordinated, tax-efficient strategy across all your assets.

Investment success isn't measured by individual account performance. It's measured by your actual, after-tax wealth accumulation. An adviser with a holistic view can structure investments in ways that are tax-efficient for your specific circumstances, recognising that different investment vehicles have different tax treatments and that your personal tax situation is unique.

They can help you understand whether PIE funds, direct shares, or other investment structures make the most sense for your position. They can coordinate the timing of income recognition, manage your exposure to FIF rules, and ensure your overall portfolio is working towards your net wealth goals rather than simply chasing gross returns.

When seeking advice, look for a fee-only, unconflicted fiduciary adviser[10]. This ensures their recommendations are driven by your best interests, not commission structures or product sales targets. A fiduciary is legally obligated to put your interests first—a distinction that matters profoundly when navigating the complex intersection of investment strategy and tax planning.

Fee-only advisers are compensated for their advice and service, not for selling particular products. This alignment of interests is crucial when you need objective guidance on tax-efficient structuring rather than a sales pitch for the highest-commission product.

The Path Forward

The DIY investment revolution isn't going away, nor should it. Access to investment opportunities is fundamentally democratising and positive. But as the New Zealand tax environment becomes increasingly complex, investors need to evolve their approach.

Understanding your total tax position, applying a tax overlay to investment decisions, and focusing relentlessly on net returns rather than gross figures—these aren't optional luxuries. They're necessities for anyone serious about building wealth in today's environment.

The supermarket aisle may be longer than ever, offering more choice than any previous generation of investors could have imagined. But choosing wisely requires understanding the true price you're paying; not just the label on the shelf, but the price after tax.

The game has changed. Make sure you're playing it properly.

Nick Stewart

(Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Huirapa, Ngāti Māmoe, Ngāti Waitaha)

Financial Adviser and CEO at Stewart Group

Stewart Group is a Hawke's Bay and Wellington based CEFEX & BCorp certified financial planning and advisory firm providing personal fiduciary services, Wealth Management, Risk Insurance & KiwiSaver scheme solutions.

The information provided, or any opinions expressed in this article, are of a general nature only and should not be construed or relied on as a recommendation to invest in a financial product or class of financial products. You should seek financial advice specific to your circumstances from a Financial Adviser before making any financial decisions. A disclosure statement can be obtained free of charge by calling 0800 878 961 or visit our website, www.stewartgroup.co.nz

Article no. 444

References

[1] Investment Company Institute, 2024 data on US ETF market share

[2] Inland Revenue Department, "Individual income tax rates" (current as of 2024-25 tax year)

[3] New Zealand Treasury, "Fiscal drag and bracket creep analysis," 2024

[4] Inland Revenue Department, "Resident withholding tax on interest"

[5] Inland Revenue Department, "Foreign investment fund rules and portfolio investment entities"

[6] New Zealand Tax History, "Top personal tax rates 1988-2021"

[7] Taxation (Annual Rates for 2020–21, Feasibility Expenditure, and Remedial Matters) Act 2021

[8] Financial Advice New Zealand, "The importance of holistic financial planning," professional standards guidance

[9] Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand, "Tax-effective wealth management strategies," 2024

[10] Financial Markets Authority, "Financial adviser disclosure requirements and fiduciary standards," Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013